Promoting LGBTQ2 mental health through an end to conversion therapy: The role of public health

Photo credit: Rachel Taylor, Centre for Gender and Sexual Health Equity

In this blog post, Dr. Travis Salway discusses LGBTQ2 conversion therapy as a public health issue and suggests actions that practitioners can take to promote positive mental health and reduce stigma and discrimination in LGTBQ2 communities.

Conversion therapy is a public health issue

Conversion therapy is defined by transfeminine scholar Florence Ashley as

|

any treatment, practice, or sustained effort that aims to repress, discourage or change a person’s sexual orientation, gender identity, gender modality [i.e., transgender], gender expression, or any behaviours associated with a gender other than the person’s sex assigned at birth or that aims to alter an intersex trait without adequate justification. [1(p7)]

|

Over 20,000 Canadians have been exposed to conversion therapy, which is associated with self-hatred, poor self-esteem, anxiety, depression, problematic substance use and suicide. [2,3] The scope and severity of ongoing conversion therapy practices have been invisible to many Canadians — including public health — in part because of the shame many survivors experience, making it difficult for them to speak up.

On December 13, 2019, Prime Minister Trudeau issued a mandate letter to the minister of justice instructing them to “amend the Criminal Code to ban the practice of conversion therapy and take other steps required with the provinces and territories to end conversion therapy in Canada.” [4] This landmark step came after years of activism and testimonies from Canadian conversion therapy survivors about the psychological pain they have endured. [5,6,7,8] As stated by legal scholar Florence Ashley about conversion therapy, “torture isn’t therapy.”[1(p1)]

Conversion therapy is just the tip of an iceberg

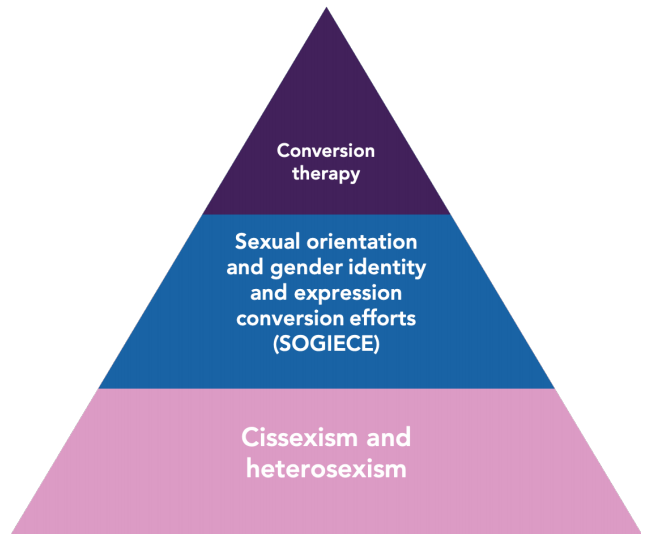

Conversion therapy is a collection of practices that represent the ‘tip of the iceberg’ (or pyramid), rooted in ongoing prevalent practices that shape everyday social environments and cause harm to the physical and mental health and wellbeing of LGBTQ2 [a] people (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The conversion therapy pyramid [5]

These ongoing practices include Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity/Expression Change Efforts (SOGIECE). SOGIECE comprise formal conversion therapy as well as broader practices that are less well defined and less advertised. For example, structured counselling as an attempt to change sexual orientation or gender identity/expression is considered formal conversion therapy. When healthcare professionals, teachers or others in positions of authority discourage expression of LGBTQ2 identities, this is a form of SOGIECE.

SOGIECE are enabled and condoned by widespread heterosexism and cissexism [b] in contemporary societies, including Canada. Despite decades of legal and social gains, LGBTQ2 people continue to face pervasive stigma in Canada today. [6,7] SOGIECE are strongly influenced by ongoing harmful messages that LGBTQ2 people receive in many parts of their lives (e.g., television, social media, classrooms, churches). Thus, groups and individuals who continue to espouse or implicitly support cissexist and heterosexist attitudes (e.g., prominent and outspoken commentators who deny the experiences and identities of trans people) facilitate SOGIECE by adding a sense of legitimacy or even empowerment to their ongoing discriminatory practices.

Fully eradicating all forms of conversion therapy, including SOGIECE, and promoting positive mental health for LGBTQ2 communities requires challenging the stigma and discrimination experienced in their daily lives.

SOGIECE is further related to Canada’s history of colonialism. Two-Spirit scholar Sarah Hunt describes the lasting impact of European-colonial residential schools on enforcing European cissexist and heterosexist norms and behaviors, reminding us that “residential schools racialized native children as ‘Indians’ while enforcing strict divisions between girls and boys through European dress and hairstyles, as well as physically separating them in different dorms.” [8(p9)] Thus, the often-traumatic experience — encompassing cultural, physical and/or psychological violence — of tens of thousands of Indigenous people in the residential school system constitutes its own form of SOGIECE.

What can public health do to reduce stigma and discrimination in LGTBQ2 communities?

1. Promote supportive social environments

In addition to banning formal conversion therapy through multiple legislative actions, public health also has another role: to address SOGIECE and to create supportive social environments to promote the mental health and wellbeing of LGBTQ2 communities in Canada. This starts with listening to survivors (those with lived and living experience) and speaking up about the harms of all conversion efforts.

Other ways to support survivors include the following:

- Survivor stories are increasingly being shared and made public. [9,10,11,12] Listen to these stories. Share them. And find ways to support other survivors’ voices.

- No Conversion Canada offers specific actions all of us can take. Follow and support No Conversion Canada.

- Contact your local Members of Parliament and Legislative Assembly to let them know that it is important to enact laws that protect LGBTQ2 people, including those that prohibit conversion therapy.

As we know from attempts to legislate other harmful behaviors, bans can only go so far, and therefore the solution is multifaceted. The conversion therapy pyramid [5] suggests the need for more broad and fundamental approaches to preventing persistent exposure to negative messages that are harmful to the mental health of LGBTQ2 youth.

2. Work with LGBTQ2-affirming partners

A key role for public health is to work with partners to ensure that Canadian youth receive comprehensive and LGBTQ2-affirming messages and resources, early and consistently throughout life, as a way to shape positive social environments.

Several initiatives are underway in Canada to increase access to LGBTQ2-affirming education and support for youth and their parents and caregivers. These include the following:

- YouthCO’s Sex Ed is Our Right campaign (British Columbia)

- Action Canada for Sexual Health & Rights, #SexEdSavesLives (available in French)

- SOGI 123

- Youth Project (Nova Scotia)

3. Learn about LGBTQ2 trauma and stigma

Public health practitioners and leaders at all levels intersect and work with members of the LGBTQ2 community. We can take the time to learn about the effects of trauma, microaggressions and forms of overt or subtle discrimination of LGTBQ2 people. Ask yourself “How does my work affect LGBTQ2 communities?” as a daily reflective action. Reach across sectors to encourage other health and non-health partners to use a similar reflexive lens is a way to demonstrate leadership in this area.

It is common for youth to express distress when they first come out as LGBTQ2, simply because they fear the reaction of the person to whom they are disclosing. [13] If they are fortunate enough to encounter someone who affirms their identity, they have a much greater chance of avoiding SOGIECE. Public health clinics and practitioners can be a safe space for LGBTQ2 people to feel affirmed in their identity. Safe spaces are created by shifting language, practices and approaches to support diverse gender identities, gender expressions and/or sexual orientations.

4. Collect data about LGBTQ2 health outcomes

Finally, collecting and reporting on health indicators and metrics that are relevant to LGBTQ2 communities is a key part of monitoring whether, when, where and how we are making progress to redress LGBTQ2 health inequities. This practice is a key recommendation of the 2019 House of Commons Standing Committee on Health’s study of LGBTQ2 health, [6,14] and is a concrete deliverable by which public health commitment to LGBTQ2 health outcomes can be measured.

In sum, we all have a role to play in ending conversion therapy and addressing the societal practices that undergird it. By educating ourselves about the particular threats to the health and wellbeing of LGBTQ2 Canadians, we can sharpen our public health practices and policies. Moreover, by advocating for affirming and inclusive spaces for LGBTQ2 people — in schools, clinics and beyond — we can stem SOGIECE and its roots. Speak out to your municipal, provincial and federal representatives to let them know that stopping conversion therapy and supporting LGBTQ2-affirming environments are urgent public health issues.

Travis Salway is an Assistant Professor of Health Sciences at Simon Fraser University and an Affiliated Researcher at the BC Centre for Disease Control and the Centre for Gender and Sexual Health Equity. We would like to thank Claydon Goering, gender and sexual diversity advisor at St. Francis Xavier University, and Riley Wolfe, X-Pride president 2019–2020, for reviewing and offering valuable feedback to this blog post.

Further information and contact

- Community Based Research Centre (CBRC) – Conversion Therapy and SOGIECE

- To get involved in Canadian research on the public health implications of SOGIECE, contact Travis Salway

Notes

[a] LGBTQ2 refers to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and Two-Spirit populations. Two-Spirit is an organizing strategy that enables Indigenous people who embody diverse sexualities, genders, gender identities and gender expressions to reconnect with venerated Nation-specific traditions that predated the arrival of Europeans to Turtle Island. [15]

[b] Cissexism is the belief or assumption that cisgender people’s gender identities, expressions, and embodiments are more natural and legitimate than those of trans people. [16] Heterosexism is the belief or assumption that heterosexual people’s sexual orientation identities, behaviors, and attractions are more natural and legitimate than those of LGBTQ2 and other sexually diverse people. [17]

References

[1] Ashley F. Model law – prohibiting conversion practices [Internet]. SSRN. 2019 [cited 2020 Mar 16];1-41 p. Available from: https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=3398402.

[2] Salway T, Card K, Ferlatte O, Gesink D, Gilbert M, Hart T, Jolimore J, Kinitz DJ, Knight R, Lachowsky NJ, Rich A, Shoveller JA. Protecting Canadian sexual and gender minorities from harmful sexual orientation and gender identity change efforts: a brief submitted to the Standing Committee on Health for the Committee’s study of LGBTQ2 health in Canada [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2019 [cited 2020 Mar 16]. 12 p. Available from: https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/HESA/Brief/BR10447600/br-external/SalwayTravis-2-e.pdf.

[3] Salway T, Ferlatte O, Gesink D, Lachowsky NJ. Prevalence of exposure to sexual orientation change efforts and associated sociodemographic characteristics and psychosocial health outcomes among Canadian sexual minority men [Internet]. Can J Psychiatry. 2020 [cited 20 20 Mar 16];1-8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743720902629.

[4] Trudeau J. Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada mandate letter [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2019 [cited 2020 Mar 16]; [7 screens]. Available from: https://pm.gc.ca/en/mandate-letters/2019/12/13/minister-justice-and-attorney-general-canada-mandate-letter.

[5] Centre for Gender and Sexual Health Equity. Ending conversion therapy in Canada: survivors, community leaders, researchers, and allies address the current and future states of sexual orientation and gender identity and expression change efforts [Internet]. Vancouver, BC: Centre for Gender and Sexual Health Equity; 2019 Dec 13 [cited 2020 Mar 16]. 23 p. Available from: http://cgshe.ca/app/uploads/2020/02/SOGIECE-Dialogue-Report_FINAL_Feb1820.pdf.

[6] House of Commons Canada Standing Committee on Health. The Health of LGBTQIA2 Communities in Canada [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): House of Commons Canada Standing Committee on Health; 2019 [cited 2020 Mar 16]. 59 p. Available from: https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/HESA/report-28.

[7] Ashley F. Submission to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health for the study on LGBTQ2 health in Canada on the matter of conversion therapy [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2019 [cited 2020 Mar 16]. 4 p. Available from: https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/HESA/Brief/BR10472186/br-external/AshleyFlorence-e.pdf.

[8] Hunt S. An Introduction to the health of two-spirit people: historical, contemporary and emergent issues [Internet]. Prince George (BC): National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health; 2016 [cited 2020 Mar 16]. 30 p. Available from: https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/emerging/RPT-HealthTwoSpirit-Hunt-EN.pdf.

[9] Gajdics P. I experienced ‘conversion therapy’—and it’s time to ban it across Canada [Internet]. Vancouver (BC): MacLean’s; 2018 [cited 2020 Mar 16]; [8 screens]. Available from: https://www.macleans.ca/opinion/i-experienced-conversion-therapy-and-its-time-to-ban-it-across-canada/.

[10] Poisson J. “Conversion therapy” survivor shares his story [audio on the internet]. [location unknown]: CBC Radio; 2019 [cited 2020 Mar 16]. 18 minutes. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/radio/frontburner/conversion-therapy-survivor-shares-his-story-1.5207493.

[11] Community Based Research Centre. Healing and learning: the current and future state of SOGICE [video on the internet]. In: Queering healthcare access and accessibility summit. Vancouver (BC): Community Based Research Centre; 2019 Oct 31 [cited 2020 Mar 16]. 59 minutes. Available from: https://www.cbrc.net/keynote_panel_ending_healing_and_learning_the_current_and_future_state_of_sogice.

[12] Muse E. Witness statement. Transcript from Standing Committee on Justice Policy: Affirming Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Act [Internet]. Toronto (ON): Standing Committee on Justice Policy, Legislative Assembly of Ontario; 2015 [cited 2020 Mar 16]. 20 p. Available from: https://www.ola.org/en/legislative-business/committees/justice-policy/parliament-41/transcripts/committee-transcript-2015-jun-03#P301_67228.

[13] Russell ST, Fish JN. Mental health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth [Internet]. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2016 [cited 2020 Mar 16];12:465–87. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4887282/pdf/nihms-789458.pdf.

[14] Ross LE, Salway T, Abramovich A, Kia H. Enhancing our evidence base to characterize and monitor LGBTQ2 health in Canada: a brief submitted to the Standing Committee on Health for the Committee’s study of LGBTQ2 health in Canada [Internet]. Toronto (ON): Government of Canada; 2019 [cited 2020 Mar 16]. 8 p. Available from: https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/HESA/Brief/BR10429277/br-external/RossLoriE-e.pdf.

[15] Pruden H. Two-spirit conversations and work: subtle and at the same time radically different. In: Devon A, Haefele-Thomas A, editors. Transgender: a reference handbook. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO Greenwood; 2019. p. 134–136.

[16] Serano J. Julia’s trans, gender, sexuality, & activism glossary! [Internet]. [location unknown]: Julia Serano; c2002-2020 [cited 2020 Mar 16]; [50 screens]. Available from: http://www.juliaserano.com/terminology.html.

[17] Rainbow Resource Centre. Heterosexim [Internet]. Winnipeg (MB): Rainbow Resource Centre; 2012 [cited 2020 Mar 16]. 2 p. Available from: https://rainbowresourcecentre.org/files/12-11-Heterosexism.pdf.