Prioritizing health equity in Hastings Prince Edward Public Health’s COVID-19 response

This Equity in Action story is distilled from an interview with Victoria Law (Social Determinants of Health Public Health Nurse) at Hastings Prince Edward Public Health. The interview took place in September 2021, and its details should be considered within the context of that time period.

|

In the fall, as more people got sick, I remember a manager came up to me. My original perception was that they would have preferred I was helping with the big demand in case and contact management, which I understood. But they said, “I’m so glad that you’re in this role,” which really validated me and the health equity work that I was doing. Because I felt at times that I was leaving my colleagues behind, and not supporting them when they were needing to call people until 8 o’clock at night... But when I had that validation, that made me feel like, okay, I’m still in the right place and I’m helping to reduce the number of people that are getting sick. |

COVID-19 arrives in the Hastings Prince Edward community and the experience isn’t the same for everyone

Early on, COVID-19 was seen as an international travel-related illness, and our focus at Hastings Prince Edward Public Health was on supporting repatriations and quarantining, not community spread. But things quickly started to change as we got into March 2020, and we had to look internally to how we would respond to COVID-19 cases in our own community. I had started in my role as a Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) Public Health Nurse the previous fall, when I began developing relationships, and now I concentrated again on those community connections.

As we entered into the first lockdown, one of the obvious groups that was disproportionately disadvantaged were people who are experiencing homelessness. We started looking at how to help them have a better shot at following the public heath messaging. What could we do with this group so they can physically distance, isolate when sick, get tested if they’re feeling sick, wash their hands, get clean masks… all those things that were out of reach? So, we worked with grassroots community partners, local social service agencies, and primary care partners to ensure that those needs were being met early on and throughout the pandemic.

We knew we weren’t  going to completely address the disproportion and disadvantage, but how could we modify the environment to reduce the difference? For example, there was a lack of safe isolation facilities for people experiencing homelessness, so working with hotels to find a place for people to stay. Unfortunately, in those very early days, everyone was so scared and hotels weren’t open, so we ended up going into an empty gym at a local recreation center and then a vacant high school gym. These were not pleasant places for people to self-isolate, so that came with its own challenges, but that was really the best that we could do with the resources that we had in our community.

going to completely address the disproportion and disadvantage, but how could we modify the environment to reduce the difference? For example, there was a lack of safe isolation facilities for people experiencing homelessness, so working with hotels to find a place for people to stay. Unfortunately, in those very early days, everyone was so scared and hotels weren’t open, so we ended up going into an empty gym at a local recreation center and then a vacant high school gym. These were not pleasant places for people to self-isolate, so that came with its own challenges, but that was really the best that we could do with the resources that we had in our community.

Once we started to raise awareness of these ongoing issues it became obvious to other members of our community that that we needed to do something to address these differences. The pandemic shone a very bright light on the differences in health outcomes for people depending on their circumstances. We used that opportunity to showcase the existing inequities and to ground it in people’s minds that this is what happens when we don’t have appropriate supports in place. The hope was to have some kind of impact on policy change – whether it was immediate or more long term.

Bringing the community together to promote equitable response

In those early days there were a lot of phone calls with not only local community partners but also local decision-makers, like mayors across our municipalities and Members of Provincial Parliament (MPPs), about where funding would be coming to respond. There was also some confusion about whose responsibility was it. Many community agencies thought that because this is a public health issue, Public Health responds to all pieces of it. We needed to work with our community partners to help increase understanding that we will work with our social services partners to ensure people are housed, but that Public Health doesn’t get the funding to house people.

Maybe it’s not Public Health’s responsibility on our own, but we do have a responsibility to help coordinate the stakeholders within our community to see how can we support people. Those community partnerships expanded, and we had regular meetings: myself, Social Services, a church with a daily meal program for people experiencing homelessness, and the shelter. When our leadership made those calls to the mayor and MPPs, it helped that they knew where the issues were and the need for funding, because our community isn’t safe if we have these gaping holes for people experiencing homelessness.

For community partners, it helped that I was a single point of contact for Public Health. I noted I was there in my SDOH nurse role, not as a health inspector, but I could refer to my colleagues if they needed guidance with the regulations. It was like a fast pass into Public Health. I could act as a liaison for our health inspector team too, and I think I also helped to support some of their health equity competencies. That’s something that we can build on in the future to ensure they continue to see how health equity is affected in their work. Some may think, I’m there to make sure that the sanitation is proper in a restaurant or nail salon. But health equity is embedded completely in that work as well — it just might not be as obvious.

Prioritizing use of community-level data and equity-driven responses

In the fall of 2020, I was able to focus on a health equity impact assessment of COVID-19 on people experiencing homelessness. I presented on it to our board of health and, once it was completed, I presented to the board again on the need and thresholds for a warming center in our community, which was based on the assessment. This health equity impact assessment helped leverage the priority across other leaders internally and demonstrated to community partners that health equity is and will continue to be a priority. And because we had this document, it helped an organization that prioritizes evidence-informed decision-making to have evidence to support the work that we’re doing, which allowed us to continue to address it.

I want to highlight the importance of gathering high-quality community-based data to shape decision-making. You can have lots of national studies or things done in various environments but having information that shows what’s going on in your community is so important, and decision-makers care about that. We know that evidence will show that health equity work is important and that it has a significant impact on health outcomes, but we need to be able to document it and show how and why that happens here.

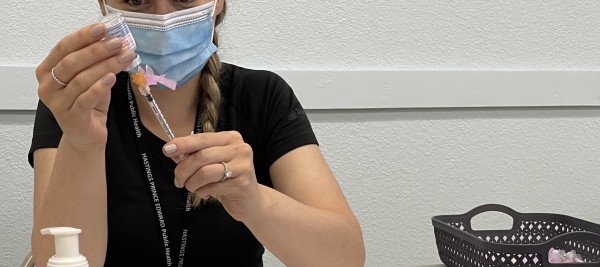

Because we made this work a priority and talked about health equity and homelessness all through the fall and into winter, it helped transition my role in support in our vaccine rollout team. I was able to provide an equity perspective that they wouldn’t have always considered in our vaccine rollout, and I hope that led to a more fair and equitable rollout from the beginning.

So, for me, success looks like having the opportunity to present community-based information to our board and stakeholders, having the opportunity to provide evidence in the form of health equity impact assessments, and continuing to have a health equity voice at the table in planning and strategic priorities.

I certainly appreciated that the leadership within our organization supported me to stay in my SDOH nurse role. When case numbers increased in the fall, there was talk of putting me into case and contact management. However, our acting Medical Officer of Health at the time really made health equity a priority. When they were doing continuity of operations in the summer planning, she made a clear point to all managers that health equity would not stop and that it was an urgent priority that needed to continue throughout the pandemic. I think that the fact that she explicitly identified it to the managers across the board left little questioning for whether or not I should continue in the role.

What’s next?

When I think of the future, I have a long health equity wish list, but we’ve got to start small. One key piece is the importance of systematically embedding health equity and health equity values into all that the organization does. That includes an equity-specific strategic plan, but also ensuring that equity is embedded into what everyone does, whether you’re a health inspector or checking people in at reception. No matter what your job is within the organization, everyone has a role to play for health equity.

Also key is making health equity training and competencies mandatory. It’s part of public health competency and practice: we are all responsible for it, and the organization needs to also ensure that their staff are supported and obtaining the training to increase their health equity competencies. I’ve heard a lot people say “that’s health equity, that’s your job, that’s not my job,” and it helps me realize that we have more work to do.

Lessons learned: |

|||

|

Supportive leadership that prioritizes health equity is essential for ensuring that health equity work continues and health equity roles are not redeployed during public health emergencies. |

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Working with community partners also involves clarifying and understanding respective roles and responsibilities, and one of Public Health’s responsibilities is to help coordinate stakeholders to support people in the community. |

||

Background:

Hastings Prince Edward Public Health is a public health agency that serves the counties of Hastings Prince Edward from four local offices in Bancroft, Belleville, Picton and Quinte West. They monitor the health of the local population, deliver programs and services within their communities and help develop healthy public policies. They provide information and support in many areas to help improve the health and well-being of their residents.

Resources:

Health equity impacts of COVID-19 on people experiencing homelessness: Executive summary

To learn more about the initiative described in this story, contact the National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, at [email protected].

Do you have an idea for an Equity in Action story? If you have heard of other health equity-promoting COVID-19 pandemic response initiatives in Canada that we should share, please let us know.